How to Spot Dyslexia, and What to Do Next

Cult of Pedagogy 2019-10-14

Listen to my interview with Lisa Brooks (transcript):

Sponsored by Pixton and ViewSonic

When I was a “regular” classroom teacher, my knowledge of specific learning disabilities was limited at best. My teacher prep program required one course in special education; it was very broad, very general, and I barely remembered anything I learned in it. This means I was woefully ill-equipped to support the students in my room with special needs—those who arrived with a formal diagnosis and those who didn’t. I mean I literally knew nothing. No special strategies. No alternative methods of instruction. My plan was to just do whatever the IEP told me to do, which mostly involved shortening assignments for those students, giving them extra time, or occasionally reading things out loud to them. I didn’t really get why these things were helpful, and I did them with limited success.

So that’s the big problem: If my experience matches those of other teachers, and a 2019 report from the National Center for Learning Disabilities says it does, then a whole lot of students are spending a whole lot of time in classrooms with teachers who have only the faintest idea of how to support them. Yes, of course every school has special ed teachers, but if students with special needs are spending more and more time in mainstream classrooms, we can’t ask the special ed teachers to be the only ones doing this work. It’s time for the rest of us to step up our game.

And a good place to start is with dyslexia.

The International Dyslexia Association estimates that as many as 15 to 20 percent of the population as a whole has some symptoms of dyslexia. This is a much higher number than I would ever have guessed, and it means that anyone who has been teaching for any length of time has probably taught at least a few students who have dyslexia, whether we knew it or not.

To learn more about dyslexia, I talked with special educator Lisa Brooks, who currently serves as Principal Director of the Commonwealth Learning Center’s Professional Training Institute in Massachusetts, a nonprofit whose programs are designed to help teachers and specialists meet the needs of students who require systematic and multisensory learning approaches. In our podcast interview, Lisa dispelled some of the most common myths about dyslexia, shared some traits teachers can look for that might indicate dyslexia in our students, and talked about some things teachers can do inside and outside of the classroom to support these students and help them be more successful.

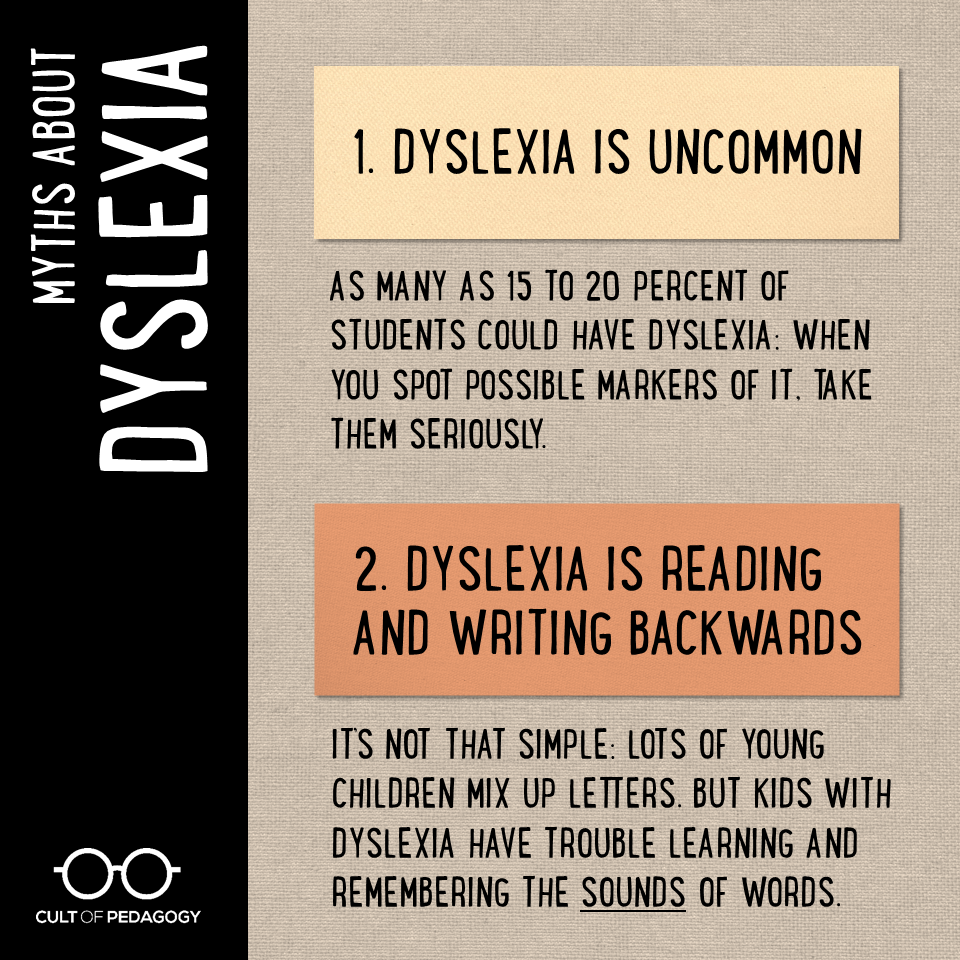

Myths About Dyslexia

Dyslexia is Uncommon

Although some educators, myself included, don’t think of dyslexia as a high-frequency learning difference, “in fact it occurs in at least 15 percent of the population,” Brooks says. With that in mind, she says, “if you have 20 students in your class, probably three of them have markers of dyslexia.”

Underestimating the prevalence of dyslexia can result in students not getting the kind of early intervention that could make a big difference. Teachers may dismiss reading and writing difficulties as attention problems or the student not being developmentally ready for certain tasks, so the diagnosis is missed or delayed.

Dyslexia is Reading or Writing Backwards

“Most children when they’re very young write letters backwards, and that is considered appropriate for 4-, 5-, 6-year-olds,” Brooks says. “But dyslexia is not writing backwards. It’s really a difficulty in the phonological component of language, and that means children have difficulty with the sounds in words. We don’t want to just say, oh, my 5-year-old is writing upside down m and w. Does that mean he has dyslexia? There’s a lot more to it than that.”

Traits that May Indicate Dyslexia

If non-special ed teachers know the markers that may indicate dyslexia in a child, we may be quicker to refer them for testing. This, in turn, can get them the interventions they need, and when it comes to interventions for dyslexia, earlier is definitely better: A recent study showed that interventions in first and second grade made twice as much of an impact as those delivered in third grade.

Here are some things to look for:

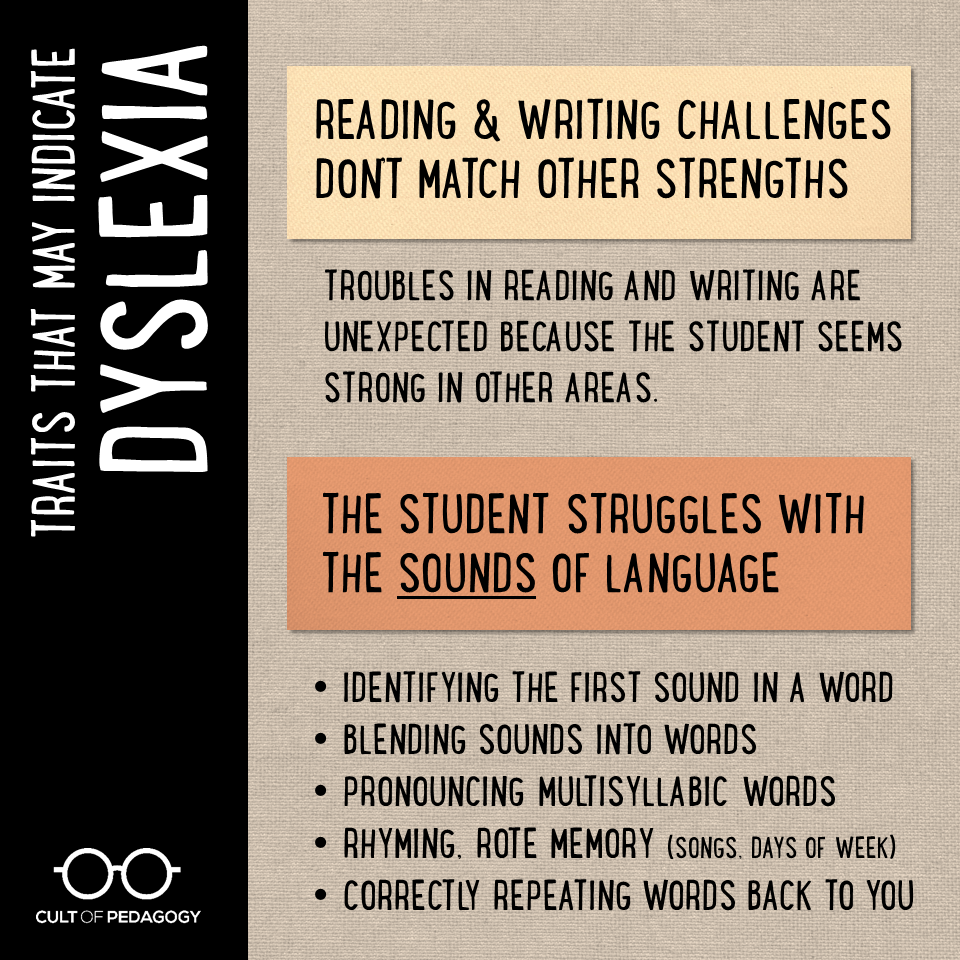

Reading and Writing Challenges Don’t Match Other Strengths

If you find yourself surprised by a student’s difficulties in reading and writing because they seem strong in other areas, that’s one potential sign that the child may have dyslexia.

“So when you look at a child who’s very verbal and good at other things, like math,” Brooks says, “and then the student is having a hard time remembering the letters in his or her own name, we say, wow, that’s so unexpected. This student speaks in paragraphs, has very high vocabulary, is interested in books, and then can’t remember a letter or a letter sound. I think that’s a first clue.”

The Student Struggles with the Sounds of Language

Although many of us tend to associate dyslexia with simply mixing up letters, Brooks says that “difficulty with the phonemes or the sounds in the language is really a marker for being at-risk.”

This difficulty with processing sounds can manifest itself in a lot of different ways. Just a few that you might see in the classroom are struggles with the following types of tasks:

- Identifying the first sound in a word

- Blending sounds into words or segmenting words into sounds

- Pronouncing multisyllabic words like “specific”

- Rhyming

- Rote memory tasks like remembering songs or the days of the week

- Correctly repeating words back to you after you say them

- Not representing all sounds in a word when spelling it

This last item, not representing all sounds in a word, bears a closer look: Consider the way two different students misspell the word butterfly. One might write budrfly, which is incorrect but still has all the sounds represented. The other, who writes burfly, is actually missing the “t” sound. This kind of omission may be an indication of dyslexia and should cause the teacher to observe this student for other signs and possibly refer them for testing.

To learn more about possible signs of dyslexia, see this list from the Yale Center for Dyslexia & Creativity.

Classroom Strategies to Support Students with Dyslexia

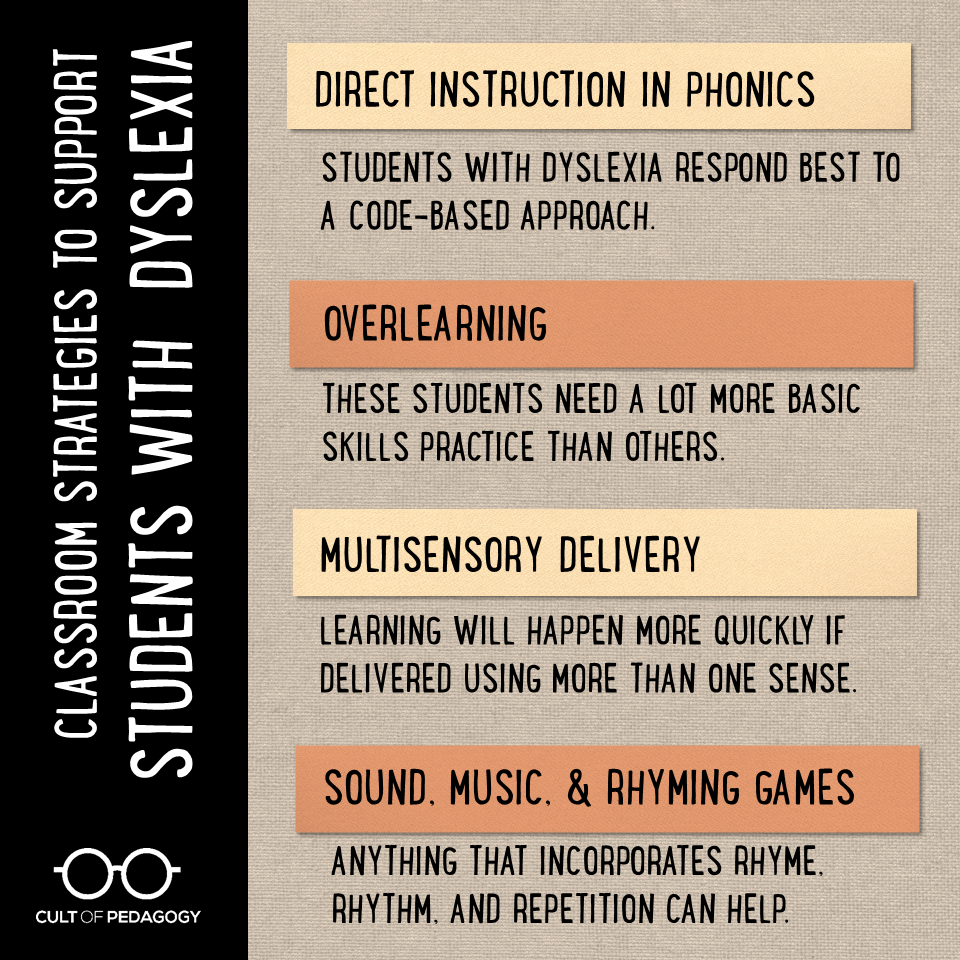

Direct Instruction in Phonics

“In terms of reading,” Brooks says, “we would say that we need a code-based approach, which really means direct instruction in phonics. Some people don’t agree with that, but really what we see in a lot of general education classrooms (is that) the 3-cueing system is not what a student with dyslexia needs. Strategies such as, look at the picture, see what sounds right, guess, see if it makes sense, those are all strategies that are not helpful to a student with dyslexia. So we really need to help them learn the code.”

Overlearning

For students with dyslexia to be successful, they need a lot more practice with skills that other students only need to be exposed to a few times.

“One of the challenges in general ed is everything moves so lickety-split,” Brooks says. “Teachers will say, ‘I taught him consonant blends.’ Well they did that for a week. Students with dyslexia need to practice and practice and practice.

“I always say, it’s like music or practicing soccer. You need to do the scales, you need to do the drills. Teachers say, well this is so boring. And I say, yes, but that’s what the student needs. They know their short vowels on Friday and they come in on Monday and act like you’ve never taught them anything; that’s because they didn’t have practice over the weekend. So we need to remember that they’re not trying to be difficult, it’s just they need a lot of practice.”

Multisensory Delivery

Students with dyslexia can learn more quickly if instruction is delivered using more than one sense simultaneously.

“So for example,” Brooks says, “when the student is writing or completing a dictation, we have them repeat the word, segment it into sounds, and they might use some kind of manipulatives to represent the sounds in the word, name the letters, and then they write the letters while saying the letter out loud. And so in that way they’re using their motor kinesthetic but also their auditory and visual at the same time. I think in classrooms we need to make sure that students aren’t just listening all the time, because we won’t get good results from that. But practicing by touching it, you know, we have them trace the letters, sometimes they’re making the letters on a whiteboard with big muscles and naming the letter as they write it. These are more strategies for our younger students, but really this multi-sensory practice is going to help it stick.”

For older students, who may be more self-conscious about using these strategies, Brooks recommends more discreet approaches, such as tapping out a word’s syllables with their fingers.

Sound, Music, and Rhyming Games

Any games or songs that incorporate rhyming, repetition, and matching syllables to rhythms can give students with dyslexia extra practice with these skills.

Find more strategies in this post from dyslexic.com.

Learn More

International Dyslexia Association

dyslexiaida.org

Tons of dyslexia resources for teachers, parents, and other professionals.

Decoding Dyslexia

decodingdyslexia.net

A parent-led grassroots movement whose goal is to raise dyslexia awareness, empower families to support their children, and inform policy-makers on best practices to identify, remediate and support students with dyslexia.

Join our mailing list and get weekly tips, tools, and inspiration that will make your teaching more effective and fun. You’ll get access to our members-only library of free downloads, including 20 Ways to Cut Your Grading Time in Half, the e-booklet that has helped thousands of teachers save time on grading. Over 50,000 teachers have already joined—come on in.

arrow_back Grįžti